The real title of this essay is 🚬🤡😳🤯, but Hugo (the tool used to generate this blog) can’t handle emoji in the title, so we have a fake title.

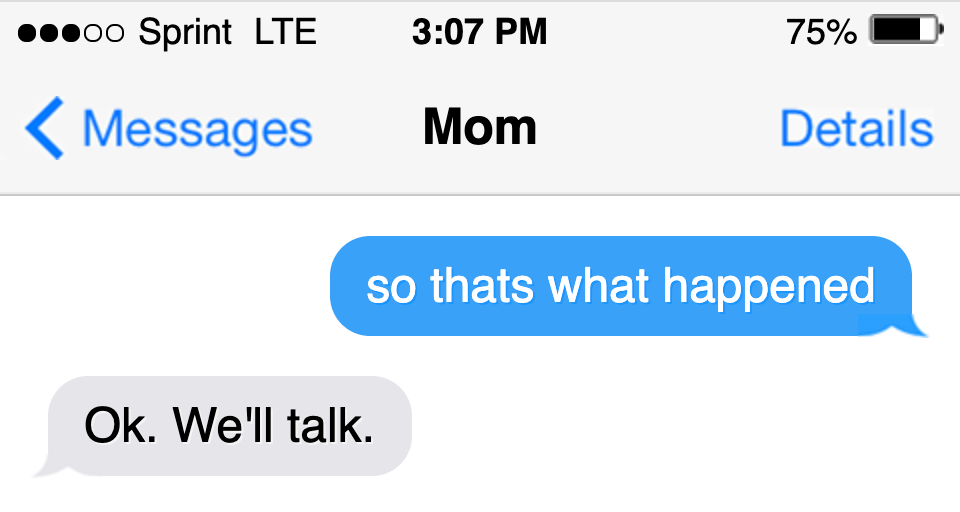

Fig 1

How does this (fake) text exchange (Fig 1) read to you? How do you read the response? To me, the response (“Mom”) is assertive and definitive. A declaration in periods. Two full stops in a short message. A refusal to react to what looks like a larger situation just out of sight if the viewer would scroll up. Some of the meaning of this text message is on the page and could easily be understood by any reader. If one is familiar with the norms of text messages, overtones of anger, withholding and judgement can be seen. Whether “Mom” intended them is impossible to say. We can modify this imaginary exchange to relieve some of the tension.

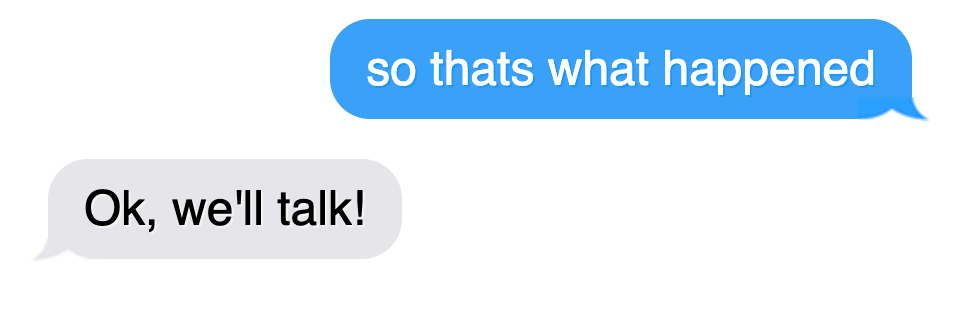

Fig 2

There’s an art to reading these texts. To understanding the nature of text messages. They are brief messages exchanged with the assumption that more will come soon. To show them in isolation like this is unfair - any person who’s used texts would know that above both of these is “what happened.” From what happened we can form opinions about the final response. That sense relies on a personal familiarity with the medium. It demands that you know that phone screens scroll up and that texts are displayed in chronological order and many other details. These are conventions of the medium that are not recorded in the “texts” of Figs 1 & 2, but would be essential for any viewer of any text message exchange in the real world.

Figure 2 is less clearly alarming, but there’s still separation in the punctuation practices of the two speakers. “Mom” is formal, using appropriate punctuation and capitalizing their sentence. It could be in an essay like this or a book. An editor would approve their sentence. They would fit within the formal confines of “writing” more so than the part of “our” explanation.

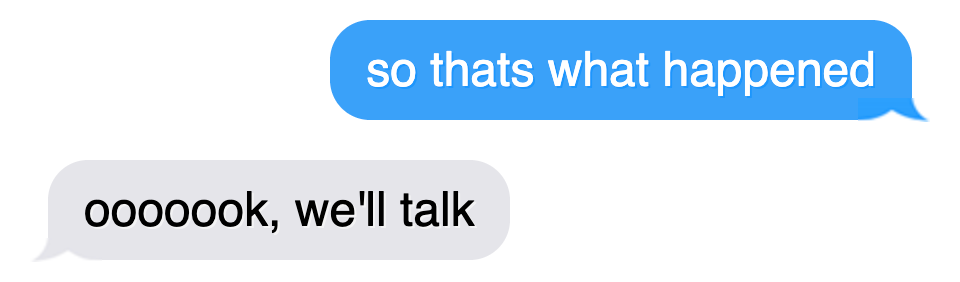

Fig 3

One more imaginary version of our exchange, this one with almost no punctuation. The emotional tone of Fig 3 might sit in the middle, but I must confess they feel increasingly similar. The “ooooook” could be read as as if it was said while sighing, perhaps while “Mom” is preparing to confront the enormity of what they have just been told. Perhaps it has overtones of bemusement; a kind of “ok buddy” but not quite that strong. Maybe the length of the “ok” just reflects the length of the story that has just been told. An attempt to respond to the length alone of what “we” have just said to “Mom” without having any judgemental comment.

Really, all of these versions have similar “texts,” but they try different strategy to communicate the affective content of “Mom"s response. In Fig 1 & 2 we might be excused if we thought that affect was communicated through characters, like those that make up the words themselves. But in Fig 3 we can see that affect is also communicated through spaces and how the words are constructed. “ooooook” and “ok” and “Ok.” are all the same word but they communicate that word with different overtones. Different affects. This affect isn’t clearly encoded - all of these different textual renderings are attempts to communicate an affect that the writer is feeling. This brief text groans under the weight of the feelings it is attempting to convey. Communication can rarely be fully captured in words alone. People learn more if they can interact over the phone or in person.

The central fiction of written material is that it cleanly links an idea in our minds to a word on the page. That it might be possible to write “ok” and have it mean the same thing as a spoken word. That writing can capture what we mean. Writing can’t do any of this because text (if you’ll excuse some hyperbole) doesn’t exist. Any time you try to write something down, you end up with a bunch of sequential images which the reader is supposed to understand as language. But as we have just spent a few paragraphs poking at, this is a silly idea. These glyphs can no more capture the full experience of language than a photo can capture the glory of a sunset. Language itself is a laughable shadow for the experience of knowing and communicating, an experience that goes far beyond our ability to communicate it.

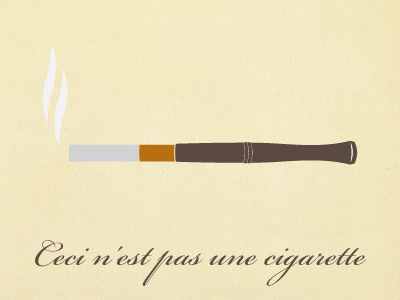

So what are these little images that are supposed to represent letters? They’re just that - images. Images which fall within a world of visual expression. I could point to the long tradition of using different fonts to evoke different emotions or the long tradition of illustrated manuscripts using different evocative ways of writing supposedly standard characters, but there’s a much more familiar way to show this.

🚬

🅴🅼🅾🅹🅸

As we will see, 🅴🅼🅾🅹🅸 represent the ultimate breakdown of the fiction of writing. Far from being the insertion of images into “text,” 🅴🅼🅾🅹🅸🆂 are an admission that text is a series of images. In addition, where traditional texts (including pictographic langauges) attempt to maintain a fiction of corresponding to the symbolic ideas that exist inside our heads, 🅴🅼🅾🅹🅸🆂 break this convention by appearing differently on different devices. The 🅴🅼🅾🅹🅸 embraces this. You’ll see one 🚬on Apple phones and a different 🚬 on Android phones. You might also see a “⍰” or a “☐” or some other indicator that the 🅴🅼🅾🅹🅸 has failed to load. But these can be deceptive! I selected those to reliably appear broken. (how would it be if they were to break incorrectly?)

In some sense, this changes nothing. Text cannot exist except as an image and it makes perfect sense for glyphs that are undeniably images to be freely mixed with letters. What realizing this allows us to do is think more openly and evocatively about how we understand writing from other ages and how to think about the impossible challenge of writing things for readers who we are sure will not share our culture.

Citations

Dean, Jodi. Blog Theory: Feedback and Capture in the Circuits of Drive. Polity, 2010.